The Major Suit of the Tarot

Center Suit

When people consider the magic and the symbolic power of the Tarot,

which is responsible for its huge impact on many generations, they

usually think about the 22 cards of the major suit. Without the

major suit we would have a deck similar to the normal playing cards:

a convenient means for games of chance and for popular

fortune-telling, but not something which could motivate centuries of

preservation, development, interpretation and creativity as the

Tarot cards have done.

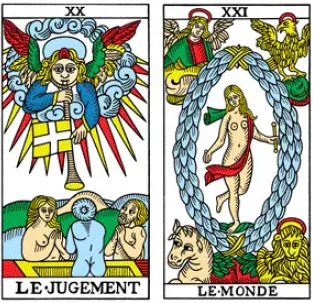

The relationship between the major suit and the four minor suits can be seen symbolically in The World card, which is the last one of the major suit. In its corners there are four living creatures taken from Biblical tradition: bull, lion, human, and eagle. These can symbolize the four minor suits and the four domains of life which are body, desire, emotion and intellect. The four figures define a solid rectangular frame, which also brings to mind the regular structure of the four suits. The dynamic element appears in the middle, in the form of a naked figure dancing within an oblong wreath. In the Tarot deck, it can represent the major suit. In the human sphere it can symbolize consciousness, which unites the different functions into a single entity.

Order & Chaos

The major suit differs from the minor suits not only in the richness

and complexity of its card illustrations, but also in its less

orderly and more chaotic structure. The four minor suits follow a

fully predictable pattern. After the 4 of cups comes the 5 of cups,

and just as there is a knight of swords, there is a knight of coins.

In contrast, the cards in the major suit display a complex and

unpredictable sequence. To demonstrate this point, let us consider a

situation where someone sees all the cards from the beginning of the

major suit up to a certain card. From this information, he would

still have no way of guessing the title or the subject of the card

which follows.

This characteristic sets the major suit apart from other systems of

symbolic illustrations which were common during the Renaissance. An

interesting example is a collection of card-like prints from the

later 15th century. They are known as Tarocchi del Mantegna (“The

Tarot of Mantegna”), although they are not really Tarot cards and

the attribution to the famous painter Mantegna is unfounded.

The Mantegna prints are divided into five suits of ten images each,

with symbolic subjects taken from the conceptual world of the

Renaissance. The five suits represent themes like professions and

social positions, liberal arts and sciences, the nine muses, moral

virtues and celestial objects. Some of the subjects are similar to

Tarot cards. For example, there is an Emperor, a Pope, and images

representing Force, Justice, the Sun and the Moon.

Still, the Mantegna prints are very different from the Tarot. First

of all, it is not even clear that they were meant to be used as a

deck of cards. In the surviving originals the images are printed on

thin paper and bound together as a book, perhaps for educational

purposes. This gives them a well-defined and single standard

ordering. In contrast, Tarot cards can be arranged and read in any

order. This means that there is an element of chaos which is

inherent to the Tarot cards already by the fact that they exist as a

set of separate images that can be freely arranged.

The more orderly character of the Mantegna prints is further

expressed in the regular structure of the five suits, none of which

are exceptional in size or structure. All the illustrations are

consecutively numbered, and each one of them has a title written at

the bottom. Moreover, when sets of symbols are used they are

presented in their completeness. For example, all the nine muses

appear consecutively without any one missing, and the same is true

of the seven traditional planets, the four cardinal virtues and so

on.

More patterns appear further along the line just to break down once again. Three major cards present, at equal intervals, three of the four cardinal virtues in Christian tradition: Justice (number 8), Force (11) and Temperance (14). But the fourth virtue, Prudence, is missing. The Temperance card presents another exception. It is the only card in the major suit whose French name is written without the definite article, “Temperance” and not “La Temperance.”

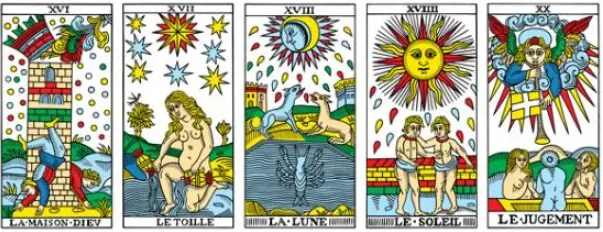

Further along the suit there are three cards with astronomical and alchemyinspired symbols: The Star, The Moon, and The Sun. Yet before them we find The Tower, with a different symbolic language whose origin is unclear. And after these cards comes The Judgment card which is again linked to Christian symbolism.

Many Tarot books over the last two centuries have tried to find a

uniform and logical order in the major suit. Some of their authors

have based their attempts on the ordering of the cards, for example

by dividing the suit without The Fool into three sets of seven

cards, or into seven sets of three cards. More complex patterns were

also tried. None of them have proved convincing enough to gain

general acceptance.

Other authors have tried to find order in the cards by imposing a

system of symbols taken from other sources. For example, many have

tried to establish a correspondence between the major suit cards and

the astrological symbols of planets and zodiac signs. But each have

notably done so in a different way. The Golden Dawn order leaders

tried to integrate the cards into their huge table of world-wide

correspondences. But again, a disagreement soon appeared as to how

exactly to do it. Apparently, in each of these schemes some cards

naturally find their place. But then there are others which do not

fit so easily, and finally there are some that really have to be

forced into their corresponding slots. Some of the correspondences

created over the years are interesting, and may enrich our

understanding of the cards. One such example is the correspondence

between the cards and Hebrew letters outlined later. But perhaps we

should not attach too much importance to any orderly table or any

scheme for the definite arrangement of the cards. The breaking of

patterns in the major suit could itself carry an important message

for us.

Scientists today speak of the phenomena of life as emerging “on the

edge of chaos,” a sort of intermediate region between chaos and

order. The perfect order is expressed by a solid crystal where

everything is well-ordered and fixed. It has no potential for

movement, and thus no place for life. The total chaos is expressed

by smoke which has no stable shape. Here too there can be no life,

because every structure would quickly dissipate. Biological and

social life processes take place somewhere in between the crystal

and the smoke. They are characterized by a certain degree of order

and stability, but also by creative unpredictability and an

occasional collapse of ordered structures.

The cards in the major suit, which express and reflect the infinite

complexity of life, can also be thought of as a system on the edge

of chaos. They show some degree of order and structure, but also

chaotic irregularities and pattern-breaking. Therefore it might be

pointless to look for an ultimate structure behind them. The only

pattern in the cards is the cards themselves.

Titles & Numbers

In the Tarot de Marseille, the number of each card appears in Roman

numerals. The notation is a long one in which, for example, 9 is

written as VIIII and not as IX. Perhaps this was done to prevent

confusion when the cards were held upside down. In new decks of the

English school the numbers are sometimes written in Roman numerals

in short notation (i.e., 9 is IX) and sometimes in modern numerals.

The numbers and titles of the major suit cards are basically the

same in both schools, but there are two differences. The Golden Dawn

leaders wanted to have more order and less chaos in the cards. For

this reason they made the two exceptional cards in the Tarot de

Marseille conform with the others. They gave the title “Death” to

Card 13, and this title appears in many decks of the English school.

They also put the number 0 on The Fool card, thus placing it at the

beginning of the suit. There are also some decks in which The Fool

is given the number 22 and placed at the end of the suit.

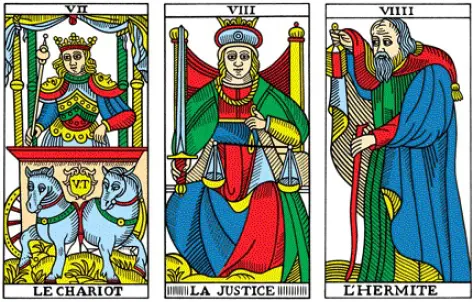

Another difference between the two schools is in the numbering of

the Justice and Force cards. In the Tarot de Marseille and in other

traditional decks, Justice is number 8 and The Force is number 11.

But in new decks from the English school, The Force is 8 and Justice

is 11. The reason for this lies in the complex system of Golden Dawn

correspondences. Putting Tarot cards, Cabbalistic texts and

astrological signs together, the order leaders came up with a

correspondence of the twelve signs to twelve cards arranged by their

numbers. Writing it down, the Justice card was correlated with the

sign of Leo (lion) and the Force card with the sign of Libra

(scales). This, however, looks strange because scales appear in the

Justice card, and a lion appears in The Force card.

The Golden Dawn leaders believed that the original Tarot possessed a

perfect order, and this anomaly reflects some mistake that crept in

during the ages. To set it right they switched the two cards. In

their system Justice became 11 with a correspondence to Libra, and

The Force, which they renamed Strength, became 8 with a

correspondence to Leo. This modified numbering became the standard

for all new decks in the English school.

Ladder of Creation

Why is it at all important to know the true ordering of the cards,

if we can place them anyway in the order we wish? The answer is that

both schools believed that the ordering of the cards was not

arbitrary. Rather, there was some message or story that the suit

sequence was meant to express.

Many Tarot interpreters, in their quest to figure out this message,

were influenced by Neo-Platonist philosophy. Neo-Platonism is a set

of beliefs which appeared in the first centuries BCE, was later

revived in the Renaissance, and also influenced the Jewish Cabbala.

According to the Neo-Platonist view the world was created in a

series of “emanations,” a ladder of consecutive steps in which the

divine plenitude or light descends. The highest level is pure

spirituality, and coming down from it the light gradually becomes

tangible and concrete. Finally it reaches the earthly level, which

is the everyday reality of matter and action.

Some of the first French Tarot Cabbalists interpreted the card

sequence of the major suit as an image of Neo-Platonic emanation.

They considered The Magician (number 1) and the following cards as a

representation of the highest spiritual level. Further on, they

claimed, the sequence of cards descends in the scale of emanation,

finally reaching the last card of the suit – The World (number 21)

which represents material reality.

The leaders of the Golden Dawn order further developed this idea.

They arranged the cards in the form of a traditional Cabbalistic

diagram, the Sefirot Tree which describes 10 aspects of the divine

essence and 22 paths connecting them. They saw the highest spiritual

degree in The Fool card, which they put at the beginning of the deck

as number 0. Therefore, in their system it appears at the top of the

tree. Then, going down the tree paths, they arranged all the other

cards by their consecutive numbers, finally reaching The World at

the bottom.

This vision also influenced the design of new decks in the English

school. For example, in the Tarot de Marseille and other traditional

decks, card number 1 (The Magician) shows a young street illusionist

in a somewhat hesitant posture. But in the Golden Dawn vision card 1

should represent a high spiritual degree, and the figure was

modified accordingly. In Waite’s 1909 deck the same card displays a

powerful magic master who looks self-confident in his commanding

authority, with the symbol of infinity hovering over his head.

Still, this reading of the suit sequence as descending from high

above to earth seems problematic if we examine the card themes more

closely. The first cards of the suit (with low numbers) show figures

whose social role and status is clear. For example, they show a

street magician, an empress, a warrior and a wandering hermit. In

contrast, the last cards show celestial bodies and nude human

figures in mysterious and imaginary situations. These include, for

example, a girl pouring water under the stars, an angel blowing his

trumpet over three figures rising from the ground, and a dancing

woman surrounded by four divine living creatures. Looking at these

images, we may think that perhaps it’s the first cards which are

earthly and mundane, while the last cards hint to a more lofty and

mysterious level of reality.

Another clue in this direction comes from the traditional use of the

cards for gaming. In old Tarot games, as in most ordinary card games

today, a card with a high number wins over a card with a low number.

The last cards in the suit have the greatest value, beating all the

cards that precede them. It is reasonable then to suppose that their

themes are meant to represent the higher levels of reality, not the

lower ones.

Such considerations motivated other authors from the French school

to adopt an opposite reading. In their view, the suit described a

ladder of reality levels which extends from the material to the

purely spiritual. But contrary to the previous reading, the suit

sequence advances from bottom to top. The first cards are earthly

and the last cards heavenly, not the other way around.

Parts of the Suit

For a better understanding of the major suit sequence and its

evolution, let us examine its different parts in more detail. Most

of the cards at the beginning of the suit show figures with a

well-defined social status or professional activity. The street

magician, the empress, the pope, the warrior in a chariot or the

wandering hermit are all figures that have their place in the social

world of the Middle Ages. Most of the figures in these cards are

large enough to fill the whole card, and they are all dressed in a

way that fits their status and occupation. Thus, at the beginning of

the suit we can see people living in normal human society.

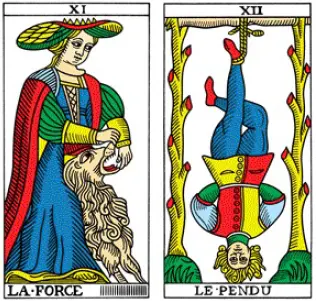

Later on in the suit, we see allegorical figures of virtues

cherished by medieval Christian society: Justice, Force, and

Temperance. The figures are still large and fully dressed, but now

they represent general ideas and not concrete people. Their actions,

such as holding a lion by the mouth or the act of pouring liquid

between two pots, also seem more like symbolic representations

rather than things that real people actually do.

To these we can add another allegory: The Wheel of Fortune which is

differently designed, but shows a traditional symbol of ups and

downs in social position. Together these cards can represent the two

basic concepts of virtue and fortune, which are very typical in

Renaissance thinking. Renaissance scholars debated the question

whether virtue, which is a person’s moral quality, or fortune, which

is capricious luck, is more important in human life. Thus, although

these four cards show abstract concepts rather than particular

people or social roles, they still operate in the earthly sphere of

human life.

The next part of the suit does not refer any more to social

positions or accepted norms. Instead, we see disruptive and

challenging cards which are detached from the common social order.

The figures in these cards have no status marks, their actions seem

mysterious or supernatural, and some of them are nude. The Hanged

Man shows a man in an unusual situation, and it is unclear whether

it expresses suffering or a choice to mortify himself. Card 13 shows

a skeleton with a sickle in a field of amputated limbs. The Devil

card with an insolent bisexual body and two tied imps mocks the

conventional norms. Even The Tower card, which at first sight might

seem to be a realistic image of lightning hitting a tall structure,

rather hints at “fire from heaven” with the mysterious reference to

God’s house in its title.

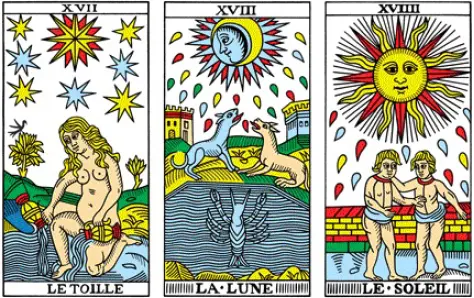

Towards the end of the suit we see another kind of change, not only

in the themes but also in the structure of the cards. Now they are

vertically divided between some action on the ground and some object

or figure in the sky. The human figures are smaller, and many of

them are partially or fully nude. In contrast to the concrete

activities or the simple allegories at the beginning of the suit, it

is now unclear what exactly the figures are doing and why they are

doing it. Who is the nude girl in The Star card and why is she

pouring water into the river? What is the relation between her and

the star which gives the card its name? And what about the two

semi-nude children under the sun, or the two dogs and the crustacean

under the moon? All of these are far removed from the common world

of practical life and simple allegories. Instead they look

mysterious, mythological and dream-like.

As in any pattern in the cards, here too there is no uniform and

orderly development. Rather it is a complex story with twists,

jumps, and exceptions. The different parts of the suit

interpenetrate each other with no clear separation between them. The

Lover card appears at the beginning of the suit, although its

structure resembles the last part: a division between ground and

sky, several small figures, and even a nude angel or Cupid.

Temperance appears at the middle of the suit as a large fully

dressed figure and in a relaxed attitude, in contrast with the

dramatic character and the nude figures of its surrounding cards.

And at the end of the suit, The World has a symmetric and formal

structure of its own which does not resemble any other card.

Closeness & Exposure

In the first half of the major suit almost all of the figures are

dressed. Some of them are also heavily covered, for example by

shawls and coverings in The Popess card, or by an armor in The

Chariot card. In contrast, many figures in the second half of the

suit are nude to some degree: partly nude in The Sun and The World

cards, fully nude in The Devil, The Star and Judgment cards, and

naked “to the bones” in Card 13. The appearance of so many nude

figures in Tarot is surprising, especially if we remember that the

cards were designed in a conservative era.

Usually, in our society nudity is associated with sexuality. But the

only card where nudity seems to appear in a sexual context is The

Devil, whose semihuman figures are lewd and shameless rather than

sexually attractive. It seems that the appearance of nudity in the

cards is not about sex. Instead, it could be linked to the idea of

social status. At the beginning of the major suit, the clothing not

only covers the body but also tells us something about the position

and the profession of the person. All the figures are dressed in a

way which expresses their social occupation: an armor for the

combatant, a royal gown for the emperor, a simple robe for the

hermit. The same is true in real life. In a traditional society

there are clear rules as to who may wear what clothes, and in our

society too one can usually guess a person’s occupation and status

by the way he dresses.

Towards the end of the suit, the signs of social status disappear

along with the clothing. Neither the names of the cards nor any

details in their illustrations tell us who these people are and what

is their social position. This removes the figures from the context

of earthly life. Interestingly, along with the removal of social

signifiers, a new structure appears in the card illustrations. Now

they show things happening on two levels: one on the ground

(earthly) and the other in the sky (heavenly).

The appearance of the sky may also signify an opening to a higher

level of reality and consciousness. It is like entering the reading

space or the circle of the magical ritual. We establish contact with

higher spheres by letting go of our mundane social identity and our

defenses, so that we stand exposed in our mysterious existence as

human being. This may be the reason why in many cultures it is

common to perform rituals of magic in the nude, or in a uniform and

simple dress which avoids all distinctions of social status.

When people enter the reading they become exposed, revealing

intimate details of what goes on in their life and mind. This is one

of the most impressive features of Tarot reading: how quickly and

intensively people open up and share contents that they usually keep

sealed and hidden, from others and sometimes also from themselves.

But doing so, they expose themselves as human beings who share the

same worries and concerns regardless of social status, wealth or

level of education. In front of the mysterious forces that we can

feel through the cards, we are all just plain humans. The nudity of

the figures may just be the cards’ way of reminding us of this.

In a reading, nudity can also be part of the symbolic language of

the cards. It can symbolize exposure, openness and the removal of

defenses and barriers. The association of nudity with a heavenly

level in the cards can also signify openness to messages from higher

spheres. In a negative sense it can be interpreted as dangerous

exposure, vulnerability and defenselessness. On the other hand,

tight and heavy clothing can signify suspicion, closure, difficulty

to let go, necessity to keep up defenses and self-preservation.

The landscape in the card illustrations can also reflect the

opposition of open and closed. An open field expresses exposure and

removal of barriers. Walls and other obstructing constructions

signify defenses and blocking. We can interpret the clothing or the

nudity of a figure in terms of attempts to keep oneself protected or

to become exposed, while the nature of the surrounding landscape can

signify the amount of openness or closure that the environment

provides.

As with any pattern in the cards, the interplay between closed or

dressed on one hand, and open or nude on the other hand, is not

linear and uniformed. Starting around the middle of the suit, after

every open or nude card there is a card with blocking structures or

dressed figures, and vice versa. In The Hanged Man (12) the figure

is dressed and blocked from all its sides by a wooden frame. Card 13

presents extreme nudity to the bones, and card 14 shows the figure

of Temperance dressed to its neck. Card 15 presents the Devil and

his imps brazenly nude, while card 16 shows a brick construction and

clothed figures. The Star (17) again presents a free and flowing

nudity in an open field, while The Moon (18) shows a blocked

landscape with sealed towers. But now a third option appears, a sort

of fusion between open and closed, with the low wall and the partial

nudity of The Sun card (19). Judgment (20) again shows nude figures,

and here even the earth and the sky open up to each other. The suit

ends in The World card (21) with a new combination of open and

closed: a nude figure, partially covered by a light scarf, dancing

inside a soft protective garland.

The Fool's Journey

We can’t know for sure the intentions of the original creators of

the Tarot. But if they did have some Neo-Platonic ideas in mind, it

seems more likely that they meant to indicate a progression from the

mundane to the heavenly and not the other way around. Examined in

this way, we can interpret the sequence as a dynamic story of

personal evolution or as an initiation quest. The story begins with

a person’s awakening from being enclosed in the earthly world of

social status and material possessions. The journey passes through

self-trials and the endurance of hardships which leads to a full

realization of human existence with spiritual awakening, openness,

and self-exposure.

In the New Age movement this reading became popularly known as “The

Fool’s journey.” The idea is that the numbered cards of the suit

represent consecutive stages of a spiritual quest. Only the

exceptional Fool card does not seem to represent any particular

stage. Instead he is the traveler himself, the person who is going

through the journey. Step by step he advances through the stages

signaled by all the other cards, finally reaching his full

realization with the image of The World.

This idea is best exemplified with the Tarot de Marseille, in which

The Fool card is exceptional because it has no number. This is

different from the Golden Dawn vision that saw The Fool (no. 0) as

the final goal of the journey, not as the person going through it.

We may also see a hint of this idea in the derivation of the name

Tarot from “The Fool’s cards.” In the cards’ language, maybe the

fool carries in his bag all the other cards, taking out each one as

he reaches corresponding stations along the way.

There were many versions of The Fool’s journey, following the first

introduction of this idea by the New Age Tarot writer Eden Gray.

Here is a version inspired by the Conver-CBD images of the Tarot de

Marseille. It is not meant to be “the true story” behind the suit

sequence, nor is it the universal model to be followed by any

spiritual seeker. The cards can be re-arranged in many possible

combinations, and anyone can find his or her own way through them.

Instead, the narrative of The Fool’s journey is a way to put in our

mind the idea of the major suit sequence as a coherent story with a

direction, sense and purpose, before going into the details of each

separate card.

The Wheel of Fortune, with the number 10 (which is significant in numerology) can be regarded as a turning point of the story. The rotating wheel can symbolize the cycles of normal life with their ups and downs. For example, it can represent the repeating cycle of working days from waking to sleep. It can symbolize a week or a year, with their regular cycles of holidays and communal gatherings. It can also stand for the cycle of generations in a family. And in Buddhist terms we can see it as Samsara, the repeating cycle of birth and rebirth.

The cards with numbers lower than 10 can represent stages of growing up in normal society. The Magician, as the number 1, represents the first awakening of our own individuality. His tools spread upon the table can stand for capacities and potentials that may or may not be realized. The four following cards are significant figures of authority that influence our early years: parents in The Empress (3) and The Emperor (4), teachers in The Popess (2), and The Pope (5).

The Lover card (6), with its unusual design for this part of the suit, turns our attention back to the individual, now coming out of his childhood years. The figure standing between two women possibly indicates the choices that we make as young adults, with consequences that accompany us for the rest of our lives. And the appearance of the heavenly Cupid in the card may symbolize the uplifting and near-mystical quality of our first encounters with love.

We can see the next three cards as a single unit. The Chariot (7) and The Hermit (9) can represent two opposites. The Justice card (8) with its scales and sword can be weighing them one against the other, as well as “cutting” and choosing between them in a particular moment. For example, we can see the serene adult figure in the middle as striking a balance between the young and the old figures on its two sides. The chariot may symbolize youthful vanity and the desire to go out and conquer the world, while The Hermit stands for maturity and a cautious outlook based on experience. Alternatively, The Chariot can symbolize an occupation with external achievements, while The Hermit indicates an inner quest for wisdom and self-awareness. The Justice card can also represent the laws and norms of society, which govern both our external actions and the shaping of our inner values.

All this is part of human life in normal society. The quest for awakening to a higher level of existence starts only after The Wheel of Fortune card. The Force (11), with a woman taming a lion whose head comes out of her own pelvis, can signify a moral battle with oneself in order to control one’s animal desires. The mysterious Hanged Man (12) carries his own self-examination to the extreme. By hanging himself upside down he is putting in question all his previous assumptions about what is above and what is below. He also takes a risk by giving up the solid base of accepted reality as he hovers above an abyss with his hands held behind his back.

The next group of cards show dramatic challenges and trials with a transformative effect. The dark appearance of Card 13 makes it stand out among all the other cards. Even its missing title may hint at things too scary to be named. The sturdy skeleton figure, the sharp edge of the scythe and the severed heads and limbs indicate disintegration and irrevocable change. The crowned head on the right can symbolize past authority figures and guiding values which are now thrown down and trampled over.

The Temperance card (14) appears as a temporary relief with gentle

reconciliation and appeasing of tensions. It may signify taking some

time to work out patiently the outcome of the extreme trial in the

previous card. It may also be needed before facing the lascivious

paradoxes and the bawdy anarchism of desires stemming from the dark

lower levels of The Devil (15). In The Tower (16) we can see the

collapse of old established structures and values, but also an

opening to higher forces coming from above. Also, it can represent

giving up high-rise vain illusions, and coming down to the humble

but fertile ground of actual existence.

The three following cards can signify together an awakened state

that comes after those trying experiences. Now life on earth are

infused with an awareness of higher levels symbolized by the

appearance of heavenly bodies above. But we can also see it as

another evolution: from the naive full exposure in The Star (17),

through the confrontation with deep and obscure layers of the mind

in The Moon (18), and finally the arrival at the balanced and

restrained acceptance of heavenly bliss in The Sun (19).

The last two cards, whose imagery is taken from the traditional Christian vision of final redemption, may indicate the desired state of spiritual consciousness at the end of the quest. In the Judgment card (20) we see the heaven, the earth and the abyss opening towards each other. The spiritual vertical axis meets the earthly horizontal axis, and the three figures can bring to mind a psychological reparation of the initial relations with the parent figures. The balanced and symmetric World card (21) is the final station of the journey, with all the elements finding their place in perfect harmony.

Still, this sublime vision can also be a trap. From a perfect

situation there is nowhere to go, no place for further improvement.

Perhaps it is better to think of the Fool’s journey not as a

straight line but as a circle repeating itself on a higher level

each time. With this vision we can interpret the strange oblong

shape between The Magician’s table legs both as an opening from

which he is born, and as an emptied form of The World’s wreath, now

perceived as a womb. As The World gives birth to The Magician, it is

time to start the journey once again.

We may also think that the very image of the cards as fixed stations

on a linear track is too restricted. Maybe it is better see it as

just one possible story among many. A richer image appears in a 1932

fantasy novel by Charles Williams called The Greater Trumps (an

old-fashioned name for the major suit cards). Williams imagines the

Tarot cards as three-dimensional golden figures. They move

incessantly in an complex dance which reflects the great dance of

life. Looking at the dance of the Tarot figures, one can understand

and predict the corresponding movements of real life events.

Amid all the dancing figures, only The Fool appears to be standing

motionless. It is said that whoever understands the meaning of this

fact will decipher the great secret of the Tarot. The secret as such

isn’t revealed in the book. But we can find a hint to it in one of

the female characters, which is a sort of an enlightened person with

all-encompassing love. Only she sees The Fool constantly jumping to

and fro, disappearing and re-appearing once again, each time filling

the empty gaps between the other cards.

Hebrew Letters

Many writers in both the French and the English school believed that

the 22 cards of the major suit corresponded to the 22 letters of the

Hebrew alphabet. This correspondence was significant for them

because traditional Cabbalistic texts attach spiritual meanings and

magical powers to the Hebrew letters. But each of the two schools

had their own method for establishing the exact correspondences.

The founder of the French tradition, Eliphas Lévi, matched the first

letter Aleph to The Magician which is the first card in the suit.

Lévi also saw the shape of the Magician’s body, with one arm raised

above and the other below, as hinting to the shape of the Hebrew

letter Alef. He matched the second letter Beth with The Popess card

(number 2) and so on, proceeding by the standard ordering of the

Hebrew alphabet.

This correspondence creates other interesting links between the

cards and the letters, some of which Lévi may have been aware of.

The letter Kaf was matched to The Force card. Kaf in Hebrew means

“palm,” like the palms holding the lion in the card. The Hanged Man

in Card 12 with his bent leg resembles the shape of the letter

Lamed. The letter Mem was matched to Card 13 which is sometimes

called Death (mavet in Hebrew). The Devil got Samekh, the initial

letter of Samael which is the devil’s name in Hebrew. The body and

the legs of the falling figure on the left of The Tower card are

similar to the shape of the letter Ayin. Lévi also put The Fool at

the place before the last, matching it with the letter Shin. This is

the initial letter of shoteh, which in Hebrew means fool. Tav is the

initial of tevel, which in Hebrew means the world.

The English school of Tarot adopted a different system. As The Fool

card was moved to the top of the suit, it was matched to the first

letter Aleph. The rest of the cards were matched according to the

sequence order, which made Beth correspond to The Magician, Gimel

(the third letter) to The Popess and so on. This correspondence may

seem strange to those who know Gimatria, the traditional notation of

numbers by Hebrew letters which is very important in the Cabbala.

For example, Beth in Gimatria is 2, but in the Golden Dawn method it

corresponds to card number 1. Nevertheless, The Golden Dawn leaders

adopted it. Later, Crowley further modified their correspondence by

switching between the letters of The Emperor and The Star.

The result is that there are different ways of matching the Hebrew

letters with the Tarot cards. This is a bit confusing because in

several new decks the Hebrew letters are explicitly written on the

cards. As some of these do it by the English system and others by

the French system, different decks show different letters on the

same card.

For an open reading on personal issues with the Tarot de Marseille

the question is not so important, as the Hebrew letters don’t

actually appear on the cards. Therefore, the whole issue can just be

ignored. Still, readers who speak Hebrew or know the Cabbala can use

the correspondences as an additional layer of meaning for the cards.

For example, there are many who believe that a person’s name has an

influence on his life. To understand the influence of a specific

name we can write it down in Hebrew, lay down the corresponding

cards in a row and read them. A similar method can be used with

Cabbalistic letter combinations which are supposed to have positive

effects. Doing this, we can create a luck-bearing talisman made from

Tarot cards. Alternatively, a card appearing in a spread can be

given a specific meaning by looking for a person or a place whose

first initial is the corresponding Hebrew letter.

If we wish to use a Hebrew letter correspondence, which system

should we adopt? A reasonable choice would be to go by the deck we

are using. With the Tarot de Marseille and other French-school

decks, we may use Eliphas Lévi’s system of correspondences. With

decks from the English school such as Waite’s, we may use the Golden

Dawn system. If you don’t know to which school your deck belongs,

it’s a good idea to check the numbers of Justice and The Force. In

the French school Justice is 8 and The Force is 11, and in the

English school it’s the other way around.